|

By John Pint

In

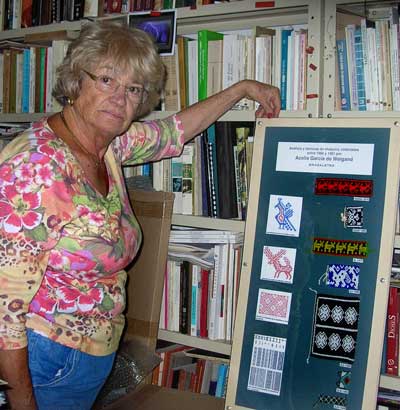

a ceremony held in the Degollado Theater on November 15, art historian

Acelia Garcia de Weigand was presented with the “Woman of 2011” award

in the field of culture by Radio Mujer which is broadcast in 386

Mexican cities. In

a ceremony held in the Degollado Theater on November 15, art historian

Acelia Garcia de Weigand was presented with the “Woman of 2011” award

in the field of culture by Radio Mujer which is broadcast in 386

Mexican cities.

Garcia is author of the

book Chaquira de los Indígenas Huicholes (Huichol Beadwork), based on

observations and collections she made during the thirty

months she and her late husband

archaeologist Phil Weigand lived with the Huicholes in the

remote village of San Sebastián Teponahuastlán, Jalisco. Nowadays the

Huicholes refer to themselves as Wixáricas (pronounced

wee-SHA-ree-kas), which, says Garcia, means “nosotros” (us).

“I was shocked,” said

the researcher when she heard about the award; “I thought they were

kidding!” These sentiments echo Garcia’s surprise in 1968 when Southern

Illinois University Carbondale asked her to teach a hands-on course in

Huichol art techniques (weaving, yarn painting and beadwork) even

though she didn’t have a degree at that time. Her expertise, in fact,

goes back to her childhood when she learned handicrafts in her village

of Tepec, Amacueca. Later, in San Sebastián, she was able to deeply

analyze local techniques and then apply this knowledge to the beadwork

collections of Carl Lumholtz, Leon Diguet and Robert Zingg as well as

her own personal collection which began in 1965 and continues to this

day.

Acelia

Garcia Weigand in 1968 in the

Southern Illinois University Adult Education News, which announced her

courses in Huichol Crafts:

Mrs. Celia

Weigand displays an example of the Huichol Indian art of Western Mexico

which she will teach this fall. The course will include instruction in

weaving, yarn painting and beadwork, with students producing their own

examples of the craft. The class wilol meet from 7 to 10 p.m. Thursdays

for ten weeks. Mrs. Weigand is the wife of SIU anthropologist Phillip

Weigand, and learned the crafts in her native Mexico.

Garcia says the purpose of her book, which is an abridged translation

of her master’s thesis at State University, N.Y., is to prove “that

these designs and techniques belong to the Huicholes of Jalisco and

Nayarit, Mexico and to make sure no one else lays claim to them.”

Beadwork and Math

Garcia went to live in

San Sebastián in 1965, originally to cook for her husband Phil Weigand

who was working on his Ph.D. on land use by the Huicholes. She spent

her days with the women, as was the custom, and became interested in

how the local designs were being transferred back and forth between

weaving, cross-stitching and beadwork. “I was so enthralled by the work

of these very intelligent women—none of whom had ever gone to

school—that I forgot all about how miserable it was sleeping on the

ground. I discovered to my surprise, that beadwork is very

mathematical.”

Ethnographers with fleas

Asked about living

conditions in the village, she reminisced: “Well, we had a down

sleeping bag with more fleas in it than feathers and we slept on the

ground and we didn’t mind. We were so happy and so interested in the

culture! The truth is, when we first arrived in San Sebastián, people

were hostile. Before going there, we had been told not to say we were

historians or archaeologists, but “ethnographers” because no one would

understand what that meant. But when we got there, we discovered that

what actually worried the local people was that Phil, being an

American, might secretly be working for a mining company and they

figured I was an escort he had rented to fool them.

Smart Huicholes

“So when we got there,

we were sleeping out in the open, but pretty soon the president of the

community came along and gave us a “room” –with no roof—in an abandoned

church that was falling to pieces. Now, they had a disused church there

because these people in San Sebastián were maybe the most traditional

of all the Huicholes…but they were smart. When a priest arrived among

them, they allowed him to make all the adobe bricks he wanted. Then

they accused him of something scandalous (It was actually not true),

threw him out and used the adobe to build their own town

hall. But we were soon accepted by the people and never had a

problem with them, only with the dogs that used to come and rob our

kitchen at night.

“Now Phil had a guide to

take him out where he could study the use of the land, while I spent

all my time with the ladies. In those days, all the Huichol artwork was

made exclusively by the women. In time, I learned a lot of

Huichol and I got along well with the women.

According to Lumholtz

"Phil had Lumholtz’s

book with him and I started reading it and I didn’t agree at all with

what he was saying! His description of their behavior was not far from

what I was seeing, but the interpretation was different. I didn’t

believe everything was symbolic, as Lumholtz claimed. You know,

Lumholtz had studied to become a priest and he was biased toward

symbolism. So Phil and I would have big discussions on this: ‘You can’t

do this and you can’t do that,’ he would say, ‘because according to

Lumholtz…’ and I would reply, ‘What does a Norwegian man know about

Huichol women? You and Lumholtz can go jump in the lake; I’m going to

do what I want to do.’ And I did it my way and I never got

into trouble.

“Most of the people who

wrote about the Huicholes focused on peyote rituals and sensationalism,

and they stereotyped the Huicholes. But in my book there is no

sensationalism. I talk about transitions of techniques, how the colors,

the designs, the weaving, the cross-stitching changed. You know,

cross-stitching done by a Mestizo woman like me and by a Huichol might

look the same on top, but if you turn it over, it looks very different.

I could see how imaginative they were, so smart!”

Acelia Garcia’s study

has never ended. “This is the fifth generation I am studying. Now one

of my sources is a policewoman at the Puente Grande Prison and she is

doing beadwork for this collection: she and her children do excellent

work.”

Garcia’s

first collection is now housed at the Museo de las Artes Populares in

Guadalajara, San Felipe 211 at Pino Suarez. It’s open Sundays 10AM to

4PM and Tuesday to Saturday, 10AM to 6PM (Tel: 3614-3891).

You can

also purchase a well-made documentary DVD in English on Acelia Garcia

and Huichol Beadwork from Explora Mexico, Tel (33) 1086 4428, Email

[email protected] .

|