|

By John Pint

In

1992, archaeologist Phil Weigand

published sketches of several

circular pyramids and a ball court he had found in the hills

above Santa Rosalía, eight kilometers north of Etzatlán. Ever

since I came across his drawings, I had wanted to visit these

ruins in the company of an archaeologist who might explain what

I was seeing. Weigand said that these ancient monuments are “in

excellent condition” but also mentioned that the climb up the

hill is very steep and you’d better bring along “water, food and

a telephone in case of emergency.” In

1992, archaeologist Phil Weigand

published sketches of several

circular pyramids and a ball court he had found in the hills

above Santa Rosalía, eight kilometers north of Etzatlán. Ever

since I came across his drawings, I had wanted to visit these

ruins in the company of an archaeologist who might explain what

I was seeing. Weigand said that these ancient monuments are “in

excellent condition” but also mentioned that the climb up the

hill is very steep and you’d better bring along “water, food and

a telephone in case of emergency.”

On top of all that, I learned from the President of Etzatlán

that one of the deepest shaft tombs ever known had been found in

these very same hills. This tomb, known as El Frijolar, measures

16 meters deep and has three large interconnected chambers at

the bottom of the narrow shaft, which is 1.5-meters in diameter.

These burial chambers have been reproduced in fascinating detail

at the Museo Oxiacar inside the Casa de Cultura in Etzatlán. The

shaft tomb was dug by the same mysterious people of “The

Teuchitlán Tradition” who—starting as far back as 2300 years

ago—built their trademark circular pyramids all over what is now

called western Mexico.

While planning my visit to Santa Rosalía, I managed to find not

just one but three archaeologists willing to participate in an

excursion to these ruins which Weigand had found atop El Peñol,

a high hill located just three kilometers north of Santa Rosalía.

I had waited for the rainy season to calm down somewhat and

finally decided to tackle El Peñol on September 16, Mexican

Independence Day. A dozen of us would-be adventurers met early

one morning outside town under an ominous sky filled with big,

black clouds.

Sad to say, even though it was a national holiday, Murphy’s Law

was still operating: just when we were ready to drive off, rain

started to fall from the sky in buckets. We were strongly

tempted to call the whole thing off, but archaeologists Rodrigo

and Cyntia Esparza had arranged for a corn-on-the-cob and

fried-fish picnic after the hike, a treat we couldn’t afford to

pass up just because Tlaloc was in a bad mood.

The head of tourism in Etzatlán had arranged a guide to meet us

in the plaza of Santa Rosalía, but hadn’t mentioned the guide’s

name. No problem, I thought, because I had expected to find the

plaza empty with only the guide waiting for us.

False assumption! As it was Independence Day, “downtown” Santa

Rosalía was jammed with people watching a parade which had just

begun. The first “float” coming down the street was a pickup

truck bearing Señorita Santa Rosalía on its hood with her Ladies

in Waiting on the roof. Next came a brand-new, shiny red tractor

pulling a nicely decorated flat trailer carrying all the old

ladies of the area, dressed in their holiday best. “We honor our

old-timers this way so we won’t forget our ancient roots,”

explained a tall and hardy young man, who, as luck would have

it, turned out to be the very person we were looking for, our

guide, Omar Preciado.

Having enjoyed the parade (which apparently included only those

two vehicles) we asked Omar about the state of the road between

Santa Rosalía and the foot of El Peñol. “It’s only three

kilometers,” said Omar. “We’ve paved part of it with

cobblestones, but a high vehicle is needed for the last

kilometer and a half.”

So it was that all thirteen of us somehow managed to squeeze

(and I do mean squeeze) into two Jeeps, which then bumped their

way along the road until we reached a clearing in a cornfield. A

light drizzle fell as we started walking up a narrow path. Along

the way, our archaeologists Rodrigo, Cyntia and Bruno Calgaro,

pointed out ancient walls and flattened places indicating that

all of El Peñol was once beautifully terraced. “These were both

for residence and for agriculture,” they remarked.

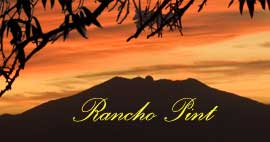

In only half an hour, we reached the top of the hill, a gain in

elevation of about 200 meters. The first ancient structure we

came to was a ball court perhaps 80 meters long. Unfortunately,

in modern times somebody decided to build a stone wall right

down the middle of it. The very fact that the ball court is

there, of course, indicates that this was a rather important

site.

A few minutes later, we saw two large circular pyramids with the

same design as the famous Guachimontones of Teuchitlán: a high

central mound surrounded by a flat, circular walkway around

which a number of platforms are evenly spaced. Two thousand

years ago, a tall pole rose from the mound, from which voladores

or bird men, attached to ropes, may have “flown,” eventually

landing on the conveniently circular runway. Perched on the

platforms had been buildings for religious or civil purposes

like visiting the bones of ancestors or paying taxes. The

walkway was also used for a dance called La Cadena, consisting

of several huge rings of dancers linked arm in arm, encircling

the pyramid.

The beauty of these monuments atop El Peñol is that they are

still intact after all these years. You don’t need an

archaeologist’s eye to recognize the mounds, walkways or even

the platforms, so the feeling that you have somehow gone back in

time is much stronger here than at sites which have been

restored. I suspect camping up here would be quite an

experience.

Our

gang of explorers pose for a group picture on the circular

walkway around a pyramid visible in the background. Hey, how

many Jorges do we have here, anyway?

“There are no dates from this Peñol,” wrote Weigand, “except

through comparative studies in architecture and ceramics.

Therefore, it is undoubtedly late Formative in date (the same as

the Guachis), and it served as a terraced fortified site

protecting one of the several accesses into the core of the

Teuchitlan tradition.” Chris Beekman adds, “If you continue up

the hill beyond the site, you will be rewarded with a little

group of constructions on the very top and a view down into the

area around Llano Grande.”

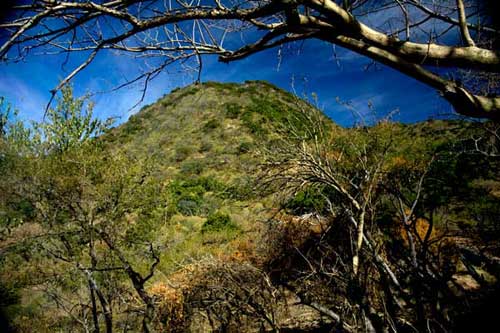

Not

surprisingly, there are a lot of copal trees on El Peñol, which

are a source of resin for incense. There is also a staggering

number of JimsonWeed plants, (Datura stramonium or

toloache in Spanish), still used today to make love potions

and worse. I wonder if these are descendants of trees and plants

used by the ancient builders of the pyramids in their

ceremonies. Not

surprisingly, there are a lot of copal trees on El Peñol, which

are a source of resin for incense. There is also a staggering

number of JimsonWeed plants, (Datura stramonium or

toloache in Spanish), still used today to make love potions

and worse. I wonder if these are descendants of trees and plants

used by the ancient builders of the pyramids in their

ceremonies.

We returned by heading south down a different path, which took

us through beautiful terraces and past a small rock mound which

may house a burial. After an extremely leisurely round-trip trek

of two hours and 45 minutes, we were back at the Jeeps and ready

for our picnic.

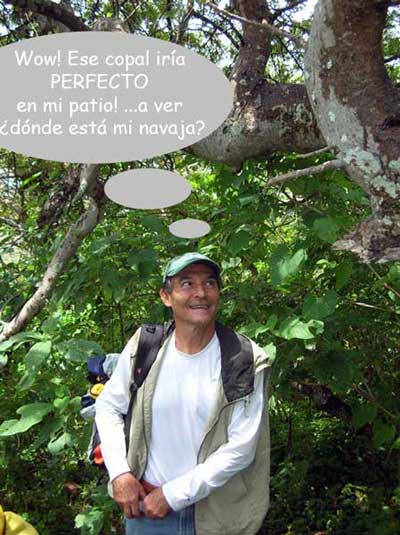

Guadalajara Muralist

Jorge Monroy

eyes a copal tree.

"Wouldn't this look

great in my patio?"

he muses while

reaching for his

pocket knife.

How to get there

You can contact guide Omar Preciado at cell phone 386-104-5632

or email [email protected] (yes, double d). To get to

Santa Rosalía, first drive to Tala. From there drive 1.4

kilometers toward Ameca and take the road to Teuchitlán and

Etzatlán. Upon arrival at the entrance to Etzatlán, turn right

onto the road to Magdalena and drive 4.7 kilometers north to San

Pedro. Proceed west from San Pedro 2.5 kilometers to Santa

Rosalía. Don’t forget your hiking or tennis shoes. Driving time

to Santa Rosalía is about 80 minutes whether from Guadalajara or

from Lake Chapala via the Circuito Sur.

|