THE

TOWN THAT WOULDN’T STAND STILL

AND OUR FIRST

LOOK AT LAVA TUBES IN HARRATS

KHAYBAR

AND ITHNAYN

� 2005 by

John and Susy Pint -- Updated September, 2013

Photos

by John and Susy Pint

It was an inauspicious

beginning. Our friend John Semple, had flown from Riyadh to Jeddah with

the plan

of buying a used Suzuki on Monday with the help of our mutual friend

Peter

Harrigan. The two of them would then drive with us the following

morning – in

that same car -- all the way to a remote town in northwestern Arabia

where large

caves had been sighted. Please note that in the paragraphs below we are

changing

the true name of this town to "Shisma" to avoid overwhelming it with

publicity (and incursions from the throngs of cavers who read these

reports). (2013: OK, I think it's now safe to reveal the

truth: Shisma is really the delightful town of SHUWAYMIS!)

It was a perfect

opportunity for Murphy’s Law to make an appearance and we were not

surprised

to get phone calls all through Tuesday notifying us of delay after

delay in the

agonizing process of buying a car. But by the end of the day, the deed

was done.

So it was that our

journey to Shisma began on Wednesday, November 6, 2002, which just

happened to

be the First of Ramadan, 1423. This meant everyone but us would be

sleeping in

extra late that morning, and we hardly saw any cars all the way to

Medina.

We proceeded northward

and when we finally rolled off the highway onto our first dirt road,

there were

still a few hours of daylight left.

A

wide track covered with powdery dust stretched before us. “This track

goes

straight to Shisma. We can’t miss it,” said our companions. “We should

get

there just in time for Iftar.”

Alhamdulillah, we

thought, because Susy and I were both dead tired. Iftar,

by the way, is

the meal that breaks the fast (which is very strict and allows no food,

drink or

even swallowing saliva all day long) and it begins exactly at sunset,

which is

announced by a cannon shot in many cities.

Well, we heard no

cannons and enjoyed no Iftar meal because, as the

sun slowly dipped below

the horizon, our wide track had utterly vanished and we found ourselves

in a

lovely but lonely plain dotted with acacia trees and surrounded by low

mountains.

“It seems like we

missed it after all,” announced our friends, who then mentioned that

they

didn't have the GPS coordinates for Shisma because it had been so easy

to find,

the first time they'd gone there.

So, Peter figured out

the coordinates from the topo map, put them into the GPS and we set out

to find Shisma in the dark, although I would have preferred to camp

right there in that beautiful spot and do our hunting in the daylight

the next morning...

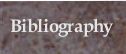

Programming coordinates as the sun

begins to set. |

|

Well, bad luck

continued to plague us because when we reached the spot which coincided

with the

location of Shisma on the map, there were no bright lights anywhere to

be seen,

only utter darkness shrouding what looked like the remains of a ghost

town. But

we could see a dim glow in the far distance and we assumed that was

Shisma.

Off we drove through

billowing clouds of choking dust until we finally came upon a few

buildings and

several human beings. We asked if this was Shisma.

“Shisma?” It’s

twenty kilometers from here, thataway. Just follow the wide track – you

can’t

miss it.”

Ah, but we could miss

it and we did, once again finding ourselves on an ever narrowing track,

winding

through sharp-edged basalt rocks and growing fainter by the moment.

“Let me

try to reprogram the coordinates from the map again,” suggested Peter..

An hour later we were

back at the ghost town.

“What else can go

wrong on this trip?” shouted John and Peter. Now, I believe this

question was

meant to be rhetorical, but the answer came literally with a bang as

one of our

tires exploded.

Next we discovered that

the ruts underneath us were so deep that there was no way to set up the

jack

without wriggling into the space between the bottom of the car and the

sharp

rocks and choking dust. It was the sort of place even a caver would

hesitate to

crawl into and, once I had squeezed underneath, I was hardly overjoyed

to

discover that our official Toyota jack required the strength of

Hercules to

crank. Well, we took turns grunting, sweating and cursing until we were

at last

able to raise the car and change that poor, destroyed tire. It was

approaching

midnight when we finally limped to the least stony spot we could find

in the

neighborhood and tried to get some sleep.

Here we present two flat tires for the

price of one. Notice how Peter's Petzl headlamp, shown on the left, can

be used for purposes other than caving, but not quite as much fun!

|

In the end, the

sumptuous Iftar meal we had dreamed of, came to

nothing but a miserable

bag of potato chips. Yes, but with a beginning like this, things could

only get

better!

In fact, a new day

dawned and we celebrated it with a truly luxurious breakfast which even

included

pancakes, whose batter Susy had prepared in advance.

Now that it was

light, we could see a town not far away and we assumed it must be

Shisma, but,

once we got there, we weren’t greatly surprised to find that it wasn’t.

“Well,

where is it?” we asked the two Bangladeshi mechanics who were busy

patching

the huge rip in our tire.

“Shisma? It’s about

twenty

kilometers from here. Just follow those power lines, you can’t…”

Well, we didn’t bother waiting to hear the rest of

the sentence and, of

course, the power lines soon went off in one direction while the track

went in

another.

But at this point, our

luck finally changed. We had flagged down an old man with a long white

beard,

who had told us we were still twenty kms from Shisma (This, of course,

was

hardly surprising to us, anymore) and who was giving us directions,

when Peter

and John happened to mention they were friends of the Headmaster of

Shisma.

The old man did a

double take, his eyes lit up and he reached out to shake our hands, as

if we

were meeting for the first time. “Hayakallah!” he said, which is a warm

greeting that bedus use amongst themselves. We had obviously moved up

to a much

higher category in his estimation and the greeting ceremony was being

repeated

in a proper bedu manner.

“I will take you to Shisma!” shouted the man as he jumped into his

truck,

even though he had been headed in the opposite direction.

At last, we broke the 20-km barrier and arrived within sight of the

Shisma water

tower, where the old man bid us Ma’asalaama. On arrival at the

Headmaster’s

house, we were greeted by his son Khalid who told us his father was out

in the

hills and was worried that we hadn’t shown up the night before. “I will

take

you there,” exclaimed Khalid, and off we went.

| Along the way, we came

to a vast, perfectly smooth area which glistened as if it were covered

with water. It was, however, a dry, tan-colored mud flat where nothing

grew and not even a stone could be found. “In this place a famous horse

race was once held,” said the Headmaster’s son,

“and that race resulted in a war that lasted

forty long years...” |

|

At last we came to a

wind-sculpted sandstone jebel where we finally met Headmaster Mamdouh

Al-Rashid,

who, from that moment on, took care of us as if we were his own

children.

Of course we told him all about the frustrating

attempts to locate Shisma.

“Ah, but Shisma is in the wrong place on all the maps,” explained the

Headmaster. “You see, we moved the town to a new location many, many

years

ago. The place your GPS kept leading you to is the old, abandoned site

of our

town.” At last, the mystery of the inescapable ghost town had been

resolved.

| ...And at last we got

to enjoy a Ramadan Iftar, which Headmaster Mamdouh,

realizing how tired we were, arranged to take place right in front of

the high sandstone jebel where we would camp for several nights...

|

|

| ...The star of the

event turned out to be a beautiful falcon whose picture was taken at

least a hundred times that evening...

|

|

“I’m going to take

you out to a dahl,” announced Mamdouh the next day.

We learned that

people in this area use the word dahl for caves

which hold water and kahf

for the dry ones. The five of us piled into the

Mamdouh'’s car along

with his young son, because it was taken for granted our poor-quality

tires

would never survive the trip!

| On our way to the dahl,

we wound our way through sprawling fields of volcanic rubble. Then we

spied a small lagoon, a sight you rarely see in Saudi Arabia, proof

that more rain falls here than in other areas we know...

|

|

...I remembered that

people had warned me about lakes in certain harrats. “There is a large,

black

water snake that is extremely vicious and capable of jumping out of the

water

and attacking people standing by the shore,” I had been told.

Fortunately,

the Headmaster assured us there were no such jumping serpents in his

area and

after a pleasant stroll around the lagoon, we drove on, past a

mountain, over

1600 meters high, until we were well inside of Harrat Khaybar, where

Saudi

Arabia's most picturesque volcanoes are located.

| Soon we arrived at the

entrance to Dahl Rumahah, which you would never find if you weren’t

looking for it. But what you do see is a long, low, curving wall built

of rocks. ...

This is just a

small section of the wall.

|

|

“This wall channels

runoff rainwater into the dahl,” explained our guide. “Once upon a time

this

cave was kept secret and its entrance hidden because it was a valuable

source of

water, a reservoir actually.”

| Headmaster Mamdouh at

the long, low entrance to the dahl ...

...and ready

to defend us against the wolves commonly found in caves like this one.

|

|

Mamdouh was

amazed we planned to go inside with our dinky little headlamps and

flashlights.

“Now, this is the kind of light you need for a cave,” he announced,

holding

up a gas lantern, which, indeed, gave off plenty of light, but was a

bit too

fragile as far as Susy and I were concerned.

As soon as we went

inside, we assured the Headmaster that his dahl is indeed a lava tube

(a point

that had been disputed). The ceiling had the classic arch and a few

small levees

here and there. Surprisingly, the cave meandered in several directions

and had a

couple of side passages.

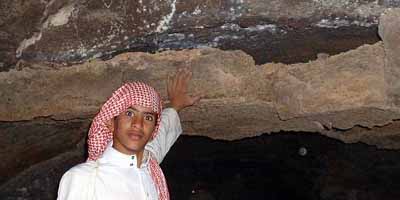

| In places, the ceiling

and walls were draped with impressive flowstone...

This is

probably calcite from leakage through ceiling cracks. As you can see,

in all these pictures we had as a model, Mamdouh's son Ahmed, who

seemed to have a natural talent for the job.

|

|

| Bones and the petrified

scat of hyenas and wolves covered the floor in some areas. ...

Click on the

picture to see how extensive this cache of bones is. Fortunately, we

didn't meet any of the creatures who had been munching on those bones.

|

|

| We also found two

“natural bridges” in this cave...

Here Ahmed

shows us the thin bridge, where you can see an intact section of the

crust that sometimes forms on top of the hot river of lava inside the

tube.

|

|

| This second bridge is

remarkable for its thickness, since the levees we've seen all point to

a crust similar to the Thin Bridge above. So why did the lava continue

to flow beneath this Fat Bridge, which must have taken quite a while to

cool?

Dahl

Rumahah may hold the answers to more than one question about

the mechanics of flowing lava.

|

|

In one area, we

came upon small pools of water and marks on the walls indicating that

once upon

a time the water level had been waist high...

| ...The humidity in this

part of the cave has left areas of the wall covered with tiny drops of

water which look like a coating of white paint from a distance ...

These drops

may be growing on a layer of "cave slime," as seen in Iceland. The

bacterial content of the slime may be very interesting.

|

|

Back in the 1980’s

Headmaster Mamdouh had measured this cave with a 50-meter long tape,

probably

making him the first person to survey a lava tube in Saudi Arabia. He

recalled

the cave as being about 500 meters long, but, unfortunately, had not

drawn up a

map of it.

We returned to our

campsite near sunset and fried our hamburgers even though we’d be

having

another Iftar just a few hundred meters down the valley. We didn’t want

the

meat to go to waste, and it didn’t. Each of us ate a hamburger and then

we

left three more of them in the frying pan, which I deliberately placed

on the

ground. As we walked toward our friends’ camp, we found their saluqi

dog along

the way, staring at our cooking area with rapt attention. “I don’t

think

those hamburgers will last long,” I told Susy, and sure enough, when we

got

back we found the frying pan licked clean. Later, however, we were told

that

this particular saluqi would never do such a thing. So we figured it

must have

been..

THE

MOUSE

What mouse?

Well, later that evening, as we sat in the dark

listening to the BBC news

on our WorldSpace satellite radio, Peter shouted

“Hey! Some animal keeps bumping into me!” I switched

on my light and

there was a cute little mouselike creature, tan and white in color with

big eyes

and a long tail. It reminded me more of a gerboa (without the powerful

back

legs) than your average mouse. Anyhow, it moved away very slowly, as if

reluctant to be interrupted while scrounging for crumbs at Peter’s feet.

The next morning,

while we were brewing our gourmet Camp Coffee, John

asked Peter a curious

question: “You weren’t eating potato chips somewhere near my cot last

night,

were you?” He had woken up and found chip crumbs everywhere inside his

sleeping bag. “It wasn’t me,” replied Peter, “but I think I know who it

was. That mouse was rattling the potato chip bag all night long and I

bet I know

exactly where he went to eat them: a nice, warm, snug place next to

you, the

world’s heaviest sleeper.”

Peter

went on to tell us how John had once slept through the Thunderstorm of

the

Century which had sent everyone but him out of their tents and into

their cars

for safety.

Over breakfast we also

heard a number of stories about four-wheel-drive Suzukis, such as the

one John

had just purchased and which had not given us the slightest problem on

this

trip. “I came upon a chap in Africa who was preparing his Land Rover

for a

trip across the Kalahari. He spoke like one who knew everything from A

to Z

about safaris and at a certain point he turned to me and cast a

disparaging eye

upon my fully loaded Suzuki.

‘Shame on you for

endangering human lives by trying to take a toy like that across the

Kalahari.

If you don’t have a Land Rover you shouldn’t even consider such a trip.’

‘Actually, I’m not

considering it because I have just come from there. In fact, I crossed

the

Kalahari in this very Suzuki and on the way I passed at least three

Land Rovers

like yours, stuck in the mud and unable to move.’ ”

| The next day we drove

off to Hazm Khadra, a scoria cone located in Harrat Ithnayn. Like Jebel

Hil, this volcano has a series of holes leading away from it, marking

the path of a lava tube....

The biggest of

these collapses stands out like a sore thumb, but is filled with dirt.

|

|

Unlike Jebel

Hil,

you don’t have to hike for twelve kms over nasty Aa lava to get there.

In

fact, we drove straight to the most interesting-looking collapse and

camped next

to it. It was our first look at a lava tube in this area.

| The entrance hole was a

long slope piled with huge chunks of basalt and reminded me of the

entrances to some of Iceland’s

biggest caves.....

Susy Pint at

the top of the slope.

|

|

...As soon as

we

stepped into the first room of the cave, we suspected this was going to

be the

biggest lava tube we had ever entered in Saudi Arabia. The first room

was really

high and ledges could be seen far above us, perhaps the remains of

enormous

levees.

| There was no time for

surveying, but I paced off 700 “big steps” from end to end and we found

several other rooms impressively high and wide, including one with a

nice round dome ceiling. As for stalactites and stalagmites, there

wasn’t much to see, nor were there any signs of the gypsum formations

we had seen in other lava tubes. There were plenty of bones, however

and in the evening we saw a few bats exit the cave..

"Cave Ghosts"

painting the wall of the dome room with light.

|

|

Walking along the

surface toward the scoria cone, we found some holes filled with dirt

and others

with short pitches promising passages below. We also saw “kites” or

stonewall corrals with one very long wall extending off for a great

distance.

Supposedly, people drove animals to the wall, which they would follow

until they

found themselves trapped in the corral. As if to corraborate

this theory,

Peter found fragments of ostrich eggshells lying on the ground. Is this

what

those ancient hunters were after?

As

we headed

back towards Shisma, we got another flat tire. This was easier to

change now

that we were experts in the business, but we didn’t feel too great

about

putting on a spare with an inner tube inside and a huge gash outside.

We then

said goodbye to Headmaster Mamdouh and drove off towards the highway in

the

usual clouds of dust. In the first town we came to, we discovered that

our luck

had truly turned. We found brand new Bridgestone tires for sale,

exactly our

size. Peter and John assured us these were far better than our Dunlops,

so we

bought them and began the long journey back home, quite delighted to

have

visited two different Harrats in one trip and to have found remarkable

caves in

each of them.

John

Pint

|